My experience of JSS Health Centre, Bilaspur, India |

| My time at JSS opened my eyes both to the difficulties of healthcare provision ...... | My time at JSS opened my eyes both to the difficulties of healthcare provision in the rural setting with finite resources and also, the ingenuity and development that can be fostered in consequence. With tribal villagers travelling in from hundreds of kilometres to access JSS’s healthcare I was reminded of the sheer privilege British citizens enjoy of having access to universally free healthcare practically at their doorstep. Efficiency was fundamental to the day-to-day practice of medicine at JSS to overcome the heavy workload, where it was usual for doctors to see up to 40 patients a day in clinic. I was made sensible of the comparatively unlimited resources us medical practitioners enjoy within the NHS, such as being able to order investigations relatively freely, having large teams to share vast workloads, as well as simply being able to use a pair of gloves without a second thought! The team were incredibly welcoming and I was able to experience a huge breadth of surgeries, many which form the bread and butter of daily practice. I was invited to assist in theatres on operations such as cholecystectomies, hernia repairs and cyst removals in both the adult and paediatric populations. With the OBGYN team I was allowed to assist in hysterectomies, D&Cs, tubal ligations and caesarean sections. I was able to learn and practice different suturing techniques, the principles of opening and closing surgical incisions as well as recognising key anatomical structures during the operations. This was a hugely valuable learning experience for me and I hope to further these skills during my surgical placements in my foundation years. |

My experience of JSS Health Centre, Bilaspur, India

- Samick Sofat

Final year medical Student, Imperial College, London

| It was another scalding hot day as we disembarked the train at Bilaspur Junction station. The journey from Kolkata had been comfortable, but long and we had whiled away the hours watching TV and chatting with the other passengers. One elderly gentleman was a retired engineer on his way to visit family who had shared lunch with us and debated politics with Alok, our resident small talker. As Dr Yogesh later told us in one of our many morning discussions, Indian trains had a way of drawing the deepest conversations about passenger’s lives. People often finish the journey having revealed secrets about themselves that their own friends and family may be unaware of. |

With the mercury sitting at a mild 45 degrees centigrade, we emerged from the air-conditioned train and were quite taken aback at how pristine the station was. This remote town had escalators, lifts and clean platforms unlike Kolkata's Howrah Junction that we had boarded at early that same day. After a few phone calls we coordinated the pickup with the driver JSS had sent for us and were on our way to the hotel we had booked in the centre of Bilaspur.

Due to the length of our stay and numbers, my three colleagues and I were unable to stay on campus for our time at JSS, which is recommended for visiting students. Instead we opted to stay in town at the (relatively cushy) Aananda Imperial. A business hotel designed for the surprisingly substantial number of white collar workers visiting Bilaspur as well as whichever local wedding or retirement party seemed to be happening in the moderately bustling town. In the morning, after breakfast, we were picked up by one of the JSS drivers and ferried to the housing estate where several of the consultants live before making a second transfer to the main campus of JSS for a total journey time of around 30 minutes. This morning commute quickly became one of my favourite parts of our stay as Alok, Tim, and I learnt about the history of JSS, its conception, its day to day operations as well as much broader topics such as health inequality and politics in India through lengthy discussions with Dr Yogesh.

With the mercury sitting at a mild 45 degrees centigrade, we emerged from the air-conditioned train and were quite taken aback at how pristine the station was. This remote town had escalators, lifts and clean platforms unlike Kolkata's Howrah Junction that we had boarded at early that same day. After a few phone calls we coordinated the pickup with the driver JSS had sent for us and were on our way to the hotel we had booked in the centre of Bilaspur.

Due to the length of our stay and numbers, my three colleagues and I were unable to stay on campus for our time at JSS, which is recommended for visiting students. Instead we opted to stay in town at the (relatively cushy) Aananda Imperial. A business hotel designed for the surprisingly substantial number of white collar workers visiting Bilaspur as well as whichever local wedding or retirement party seemed to be happening in the moderately bustling town. In the morning, after breakfast, we were picked up by one of the JSS drivers and ferried to the housing estate where several of the consultants live before making a second transfer to the main campus of JSS for a total journey time of around 30 minutes. This morning commute quickly became one of my favourite parts of our stay as Alok, Tim, and I learnt about the history of JSS, its conception, its day to day operations as well as much broader topics such as health inequality and politics in India through lengthy discussions with Dr Yogesh.

| If you have never visited India before or you haven’t had much experience on the roads there, this will be a quintessential experience. A narrow road carries traffic to and from Ganiyari with slow moving and larger vehicles blockading the whole lane, leaving only enough room for dangerous and erratic overtaking manoeuvres as you weave in and out of oncoming traffic. This led to several near misses as suicidal drivers on two wheelers passed too close for comfort considering the speed and lack of protection their vehicle afforded them. As we pulled into the campus for the first time I was taken aback by the size of the whole operation. The site is made of a pleasing red brick and I was interested to learn that even this choice was a conscientious decision. The buildings were designed as they were to reduce the paranoia and suspicion associated with modern healthcare by the population that frequented JSS. I was even more interested to learn that this medium sized clinic by western standards covered a population an order of magnitude greater than several of the largest hospitals in London combined. With a total coverage of 1.5 million residents of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh, the limited number of beds were stretched to the limit 100% of the time. |

| Outside both the outpatient centre and booking reception, stretched a large queue of patients hoping to be seen during that day’s outpatient clinic. This was not like any other queue I had ever seen. The waiting area for the OPD was more likened to a campsite than a doctor's waiting room. People had bedding, cooking utensils and food supplies and were often accompanied by several members of their family. This was a part of the patient journey (more literally than figuratively) that Dr Yogesh emphasised on an almost daily basis. The cost of travel and opportunity cost (in terms of income lost) of attending JSS was often too high for many of these people to attend until the illness had progressed to the point of being debilitating. People were having to wait in line for upwards of a week in addition to undertaking journeys taking in excess of days and costing more than the household’s entire weekly income. All this effort to be seen in the ever-surging outpatient department. The disruption this had on their lives was almost too much in some cases and often illness was left alone until it was too late. As someone trained in a system of relative plenty, this experience could only be described as a medical culture shock. |

|

During our time at JSS we were split between the OPD, surgical theatres, the wards, and ITU. Each department has a sliver of the resources that we can play around with in British hospitals yet they manage to achieve successful outcomes from their healthcare all the same. This highlights the essence of JSS, trimming the fat from the for-profit medical practices growing abundant in India and providing the highest quality care achievable at an almost unachievable low cost. The environment and in which JSS operates breeds a unique experience of medicine where you will see rare and, in some cases, unique conditions.

Our memorable experiences at JSS were not confined solely to working hours. One evening having missed the car back to town we were forced to take one of the auto-rickshaws back (another quintessential Indian experience). We had seen several of these outsized ‘autos’ on our commute to and from Ganiyari. They were far larger than normal autos found in the city centres of India’s major cities and we were also quoted a price far lower than expected. It later became obvious that we had been foolhardy and complacent with India and all was not as it seemed. These larger autos were not for private higher but actually acted more like buses ferrying people to Bilaspur. As we puttered down the road to town we picked up first a girl and her mother, followed by an elderly man carrying some luggage followed by a family of 5! All in all, 15 people fitted in this auto that was no larger than a small hatchback as we travelled down the aforementioned dangerous road to Bilaspur.

Our memorable experiences at JSS were not confined solely to working hours. One evening having missed the car back to town we were forced to take one of the auto-rickshaws back (another quintessential Indian experience). We had seen several of these outsized ‘autos’ on our commute to and from Ganiyari. They were far larger than normal autos found in the city centres of India’s major cities and we were also quoted a price far lower than expected. It later became obvious that we had been foolhardy and complacent with India and all was not as it seemed. These larger autos were not for private higher but actually acted more like buses ferrying people to Bilaspur. As we puttered down the road to town we picked up first a girl and her mother, followed by an elderly man carrying some luggage followed by a family of 5! All in all, 15 people fitted in this auto that was no larger than a small hatchback as we travelled down the aforementioned dangerous road to Bilaspur.

| It would be extremely cliché to say that visiting JSS changed my life but it would be a lie to disregard the impact it had on me. From the moment I started medicine I had the intention, as many of my selfless colleagues share, to take part in providing care to an underserviced community. I had assumed that I would join one of the common and famous institutions that specialise in such provision such as MSF but now having spent time in Chhattisgarh I have no doubt that I will make every effort to return. In the 17 years since its inception, JSS has made strides towards its key objectives. Yet I feel there is, as always in the medical field, huge room for improvement which, in part, drives my desire to return as I gain experience throughout my own medical career. And I hope that I can play a meaningful part in something as important as what JSS is aiming to achieve in the heartland of my country. |

My experience of JSS Health Centre, Bilaspur, India

- Julian Purdy

FOJSS Volunteer Medicine Internships Abroad | “Welcome to the real world”, Dr Yogesh Sir sighed after I had given him an account of what I had discovered during my first three weeks JSS, and indeed, in India. Conversely, this place felt like a different universe compared to what I knew to be the ‘real world’, but that wasn’t entirely a bad thing. Having done my fair share of travelling in the past, namely backpacking through China, South America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa etc. I have always been in search of a place that truly was an escape from the ‘real world’, where you truly felt the distance from home, as opposed to what we now know as a lengthy flight and a couple of awkward transfers. Globalisation, the advent of the internet and social media pose a double-edged sword in this respect: Of course it’s great to be able to call home without worrying about roaming charges and facebook’s a convenient time-killer wherever you are, but as a result, can you ever really get lost somewhere with this overwhelming connectivity at your finger tips? It’s tricky. |

| My generation was brought up on the radical notion that having fun, whether it be through exploring different cultures, meeting new people or seeing something interesting, isn’t satisfactory on it’s own – you have to demonstrate to others that this is the case. Hence why there’s such an emphasis on recording every moment when you go somewhere new or try something different. Of course it’s nice to have memories, but the pressure to document your travels and experiences in the most impressive way somewhat blunts the experience. However, what happens when the reality defies, and surpasses, the contents of a photograph? This paradox became quite clear to me as soon as I entered the establishment. Hungry and tired, I arrived at JSS at 11.30pm after a 3 hour taxi journey from the airport, covering 120km and costing only 2000 rupees (£25) – not bad compared to black cab charges! I was escorted to my room by the security guard, although given the number of people lying on the grounds of the health centre, I assumed security wasn’t too tight. I initially supposed my lodgings were basic but adequate – a single bed with a modest mattress and a fan suspended above it – although I soon realised that in terms of space and privacy, I had been afforded a very good deal. Coming from a country wherein a small spider creeping in the corner would be enough incentive to sound the alarm, the insects hopping and flying around the place were something that required a few days (and sleepless nights) of adaptation. However, I soon found that if I minimised the light exposure, and kept my distance, they would also keep theirs. | Exploring different cultures, meeting new people or seeing something interesting... |

| JSS had all the investigative technology that we did back at home: An ultrasound machine, echocardiogram, X-ray, a modern HDU, extensive labs, you name it! | Over the coming days, I would realise that these people lying on the floor at night, along with the numerous stray dogs and free-roaming cows (who are protected from hunting and eating by law), were in fact patients or families of patients, who had travelled up to hundreds of kilometres from their small, isolated villages in search of the reputably honest and affordable care of the JSS practitioners. This image fitted together with my preconceptions, narrow-minded though they were, of what a rural health centre in central India would be like – crowded, old-fashioned and resource-deprived. Although in some respects I will admit this notion wasn’t too far off the mark – the general aesthetic of the establishment was a far cry from the reflective floors and asceptic interiors of the RVI in Newcastle – the presence of WIFI in all buildings and a sophisticated online patient documenting system caused me to question how archaic this establishment really was. Further, aside from certain amenities that one would only expect in the larger UK hospitals, such as MRI and CT scanners, endoscopy centres etc. JSS had all the investigative technology that we did back at home: An ultrasound machine, echocardiogram, X-ray, a modern HDU, extensive labs, you name it! |

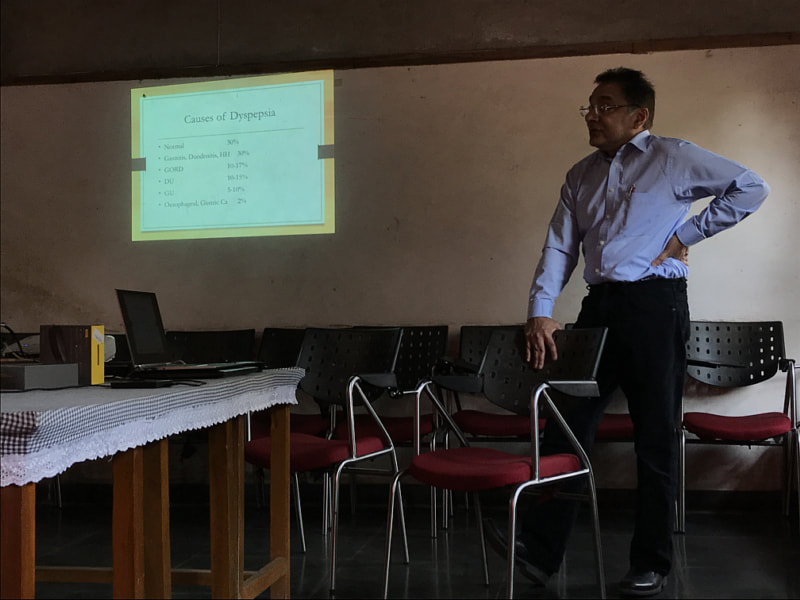

I split my time at JSS between outpatient departments, operating theatres and the wards. Patients registering would be assigned an outpatients department to wait at based on the general theme of their complaint. These departments included (but weren’t limited to) to general medicine, paediatrics, obs and gynae, surgery and psychiatry. I was astonished by how the crowded chaos at the registration building was transformed into the conveyer belt-like orderliness that I witnessed in each individual OPD. This was as much due to the patients’ patience than the hospital’s organisational ability. Imagine, having carried your ailment countless kilometres from home, at great personal cost, and slept on the floor over night, and then you’re crowded into a stuffy waiting room with a hundred other patients hoping to see the doctor that day, unsure how many hours you’ll be there, and what your condition could mean.

| In England, I envisage this scene would devolve into anarchy, with disgruntled patients shouting over each other about how their problem is the most urgent and that they have a bus to catch at 4 or a yoga class at 5. Here, however, the waiting room is silent. The reverence shown to those who work at JSS is astounding, as though patients’ haven’t been let it on the secret that healthcare is a right, not a privilege. Perhaps in this part of the world that isn’t the case. Perhaps the respect for and unquestioning obedience to the doctors is earned, as the patients here realise that any doctor who works here has made a conscious sacrifice – that of an easier, more luxurious and more affluent life. The doctors who work here have attained degrees from the best medical institutions, and their knowledge and skills are equally respected and coveted by the richest and poorest alike. And yet they choose to come to a place and people forgotten by the rest of society, and serve those who’s need is the greatest. However, maybe the need of the doctors to treat is equally as strong as the need of those to be treated? Maybe their decision to toil at their trade in an area beset with socioeconomic difficulties is less of a resentful capitulation to their social conscience, and more of a spiritual calling, that breeds inner peace? | The reverence shown to those who work at JSS is astounding. |

| I can’t help but feel that the job of 10 surgeons at home, each having trained for years in their own specialty, is being performed over here by just one! | There is one full-time surgeon on-campus, and that is Dr Raman Sir, a fellow founder and a man who redefines my understanding of general surgery. With the help of a few assistants, and the occasional guest surgeon, it seems to me that he can tackle any surgical problem that comes through the doors. I have witnessed gastrostomies, gastro-jejunostomies, colostomies, nephrostomies, nephroplasties, hysterectomies, mastectomies, hernia repairs, fistula repairs, malrotated gut repairs, cyst removals, abscess debridements, pulmonary decortications, skin grafts, TURPs, the list could go on and on! I can’t help but feel that the job of 10 surgeons at home, each having trained for years in their own specialty, is being performed over here by just one! It leaves you in awe of the remarkable achievements that can be made in a low-resource setting such as this, but equally it makes you question whether things are being done efficiently back at home, with a £130 billion budget but a national health service still supposedly ‘in crisis’. |

| Much like any other elective student travelling to an exotic, far-flung part of the world, I anticipated that I would be thrust in at the deep end, with responsibilities beyond my experience and a steep learning curve. At JSS, however, I soon realised that my role would be one of observance, and that my contribution to the every day running of the health centre would be minimal. Aside from my own low ranking in the medical hierarchy – being just a lowly medical student – the main barrier which impeded my ability to assist was the language: Even to have a grasp of Hindi (which I didn’t) was insufficient in this area, wherein a majority of patients spoke Chattisgarrhi, the local dialect. Although a little deflating at first, I soon came to appreciate the opportunity this provided for hassle-free learning: I had free reign to float between OPDs, wards and operating theatres, ensnaring any learning opportunity like a cunning thief! The doctors were more than happy to translate the pertinent information from any case, and I found myself increasingly able to corroborate my differential diagnoses with theirs. Indeed, having the luxury of sitting back and contemplating the information a patient gives you (history, examination, investigations etc.) without the need (or ability) to communicate, record and resolve affords one the opportunity to start creating mental diagnostic pathways which take up permanent residency! And at this stage in my learning, taking a break from constant assignments and assessments and instead focus on the crux of the matter – the patient – leads to crucial epiphany-like moments where you begin to realise that the knowledge you crammed into your brain prior to pass an exam is suddenly becoming relevant and contextualised, and the impossible dream of becoming a full-fledged doctor who can actually make a difference in the world realises itself as a visible – and reachable! - spec on the distant horizon (figuratively speaking). | I soon came to appreciate the opportunity this provided for hassle-free learning: I had free reign to float between OPDs, wards and operating theatres, ensnaring any learning opportunity like a cunning thief! |

| I hope to escape here again as a qualified doctor, hopefully armed with a little more Hindi, so that I may fully contribute my service where the need is greatest. | On an irrelevant side note, a guilty pleasure of mine was engaging in the amenities intended only for doctors but afforded to myself, as that was the category I was affiliated closest with, namely: Being called ‘Sir’ by all the staff (after meagrely denying the title a couple of times, I soon gave in to the ego-trip and responded with a smiling nod and a ‘good morning/afternoon’ in return) and the regular cups of chai tea and coffee kindly served by the men working in the canteen, who’s presence were rewarded with overly-enthusiastic celebration and gratitude from myself! Circling back to my original point of escaping from ‘My’ real world to ‘The’ real world, it is my belief that, after having spent a month here (hardly an adequate amount of time to postulate on such matters, but I shall do regardless), it is the combined senses of purpose and necessity which provide that escapism-real world juxtaposition. To elaborate, the necessity for health care and medical expertise is so great here, that any external inputs from the outside world become unimportant and irrelevant, as nowhere else could possibly require your efforts more than those who flock here in their hundreds every day. Additionally, and consequentially, your purpose, and the purpose of the entire workforce, becomes singular and united: If those with the greatest need are here and in need of your help, then who else and what else matters? It is this shared mantra that pulses through JSS like a life force, and the camaraderie and team spirit it creates between those who work here is palpable. So appealing is this prospect, that one day I hope to escape here again as a qualified doctor, hopefully armed with a little more Hindi, so that I may fully contribute my service where the need is greatest. |

My experience of JSS Health Centre, Bilaspur, India

-Alok Prasad

Final Year Medical Student

Imperial College, London

| Coming from a (relatively) well-resourced healthcare system to the unforgivingly hot and rural destination of Bilaspur certainly gave us a lot to ponder. I don’t think I’ll ever forget the scene of rolling into work, in the hospital jeep - to scores of people camping outside the hospital complex. Only then do you realise what real medicine and really being a doctor is about. When Dr Yogesh told us that the hospital caters for around 1.5 million people, I didn’t quite believe him but what’s more amazing is how such a small team manages it. A lesson I learnt from the experience was how resource-conscious all the staff had to be - whether it be reusing clinical gloves or autoclaving instruments, or being very judicious in the choice of medical tests and investigations. It really showed the clinical skills of all the doctors, that they would correctly diagnose many conditions in the absence of certain tests. Indeed, when Sushil (basically the fixer of the whole place) showed us around the applied technology unit, I was honestly taken aback by the ingenuity of the whole operation. Spacer devices in the UK for respiratory conditions that cost an arm and a leg, had been replaced by a sealed metal tumbler. Simple, effective and cheap - we could certainly use a dose of that kind of lean thinking in the NHS. |

JSS is not just a hospital, but an organisation dedicated to improving all aspects of the health of the rural poor. I certainly was surprised to see that a huge amount of time and effort was devoted to improving agricultural standards. Things that we take massively for granted in the EU Common Agricultural Policy-laden fields of England! The instruction given to farmers about how to improve crop yields, soil quality and grow foods that have greater nutritious value were an extremely simple but effective way of improving the health of the population. And considering just how many medical consultations I had seen, in which malnutrition was the usual cause of the problem - this was prevention in action.

My experience of Community Centre, Bilaspur, India

-Tim Hall

Final Year Medical Student,

Imperial College, London

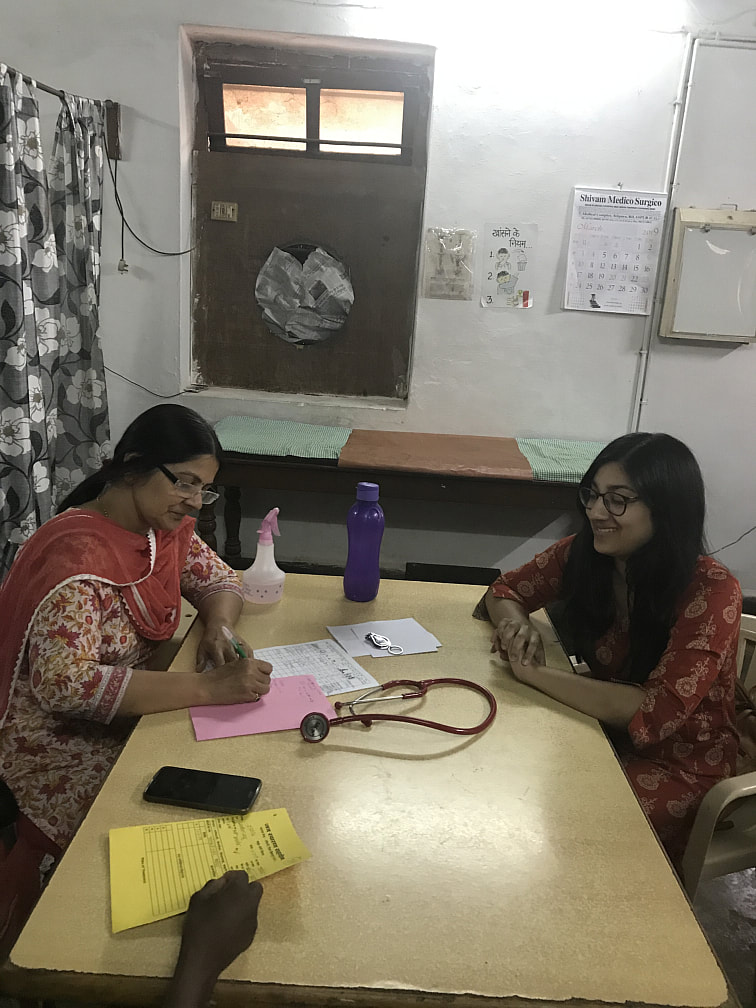

| It’s a Saturday morning on the JSS campus and this morning we are driving out to visit the community centres where doctors hold their weekly clinics. From the Jeep’s rear seat, I peer out across the northern Chhattisgarhi farmlands – the pace of life is quieter compared to the bustle of Bilaspur and Ganiyari. We hop off the jeep at the community clinic and have a quick tour of the centre. A sheltered area where all of the notes are kept, a kitchen, a basic laboratory and finally the consultation room. It is a small centre but busy nonetheless with patients sat out in the yard waiting their turn to be seen. I seek refuge under the ceiling fan which blows a cooling breeze as the first patients are seen. |

Patients come in with all sorts of maladies ranging from arthritis to old TB. A lady presents with a severe pain in her ear which has now led to tenderness around the jaw and mastoid. The team suspect an infection which has now progressed. The nurse and doctor help her into the adjoining room where she can lie down, set up an IV and await the ambulance to transfer her back to JSS.

Throughout the morning the patients calmly wait outside in the yard, some peering through the doorway to watch the doctors’ clinic, recognising each other and sharing jokes between themselves. There is a strong sense of community and a very welcoming atmosphere.

After a busy morning clinic, it’s time for lunch!

We’re served generous portions of fresh rice and dahl sitting on the floor in the centre. I’m not accustomed to eating with my hands so I manage to find a fork from somewhere and wolf down the delicious food.

Throughout the morning the patients calmly wait outside in the yard, some peering through the doorway to watch the doctors’ clinic, recognising each other and sharing jokes between themselves. There is a strong sense of community and a very welcoming atmosphere.

After a busy morning clinic, it’s time for lunch!

We’re served generous portions of fresh rice and dahl sitting on the floor in the centre. I’m not accustomed to eating with my hands so I manage to find a fork from somewhere and wolf down the delicious food.

FOJSS

UK Medical Student Internships Trainee Blog

Archives

February 2019

October 2017

May 2017

March 2017

January 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed